- Home

- Irin Carmon

Notorious RBG

Notorious RBG Read online

Dedication

To the women on whose shoulders we stand

Contents

Dedication

Authors’ Note

1. Notorious

2. Been in This Game for Years

3. I Got a Story to Tell

4. Stereotypes of a Lady Misunderstood

5. Don’t Let ’Em Hold You Down, Reach for the Stars

6. Real Love

7. My Team Supreme

8. Your Words Just Hypnotize Me

9. I Just Love Your Flashy Ways

10. But I Just Can’t Quit

Appendix:

• How to Be Like RBG

• RBG’s Favorite Marty Ginsburg Recipe

• From “R. B. Juicy”

• From “Scalia/Ginsburg: A (Gentle) Parody of Operatic Proportions”

• Tributes to the Notorious RBG

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

About the Authors

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Authors’ Note

HI, IT’S IRIN. A book is always a collaborative process, even when there is only one name on the cover. And this one has two, so I thought I’d introduce the two of us and tell you how we did it. Shana, then a law student, created the Notorious R.B.G. Tumblr as a digital tribute to Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and she sparked an international phenomenon. I’m a journalist who interviewed RBG for MSNBC and will not try to wedge any more initials into this sentence. We are both #millennials who like the Internet but wanted to make something you could hold in your hands—or at least keep on your device for longer than a browser tab. We both researched and reported the book; I wrote it, so if you see “me,” that’s Irin. Shana also curated the images and fact-checked. We drew on RBG’s own words, including my interview with her in February 2015, as well as our interviews with her family members, close friends, colleagues, and clerks. We also dug deep into RBG’s archive at the Library of Congress. (You can skip to the end if you want to see her doodles during a conference in 1976.) We cite in the endnotes where we have gratefully relied on the reporting of others. Justice Ginsburg met with me in May 2015 to fact-check parts of the book, which involved both her patient generosity and my getting to text my boyfriend that a U.S. marshal was coming for him.

In homage to the Notorious B.I.G., the chapter titles in this book are inspired by his lyrics. We thank his estate and Sony Music for permission to use them. Artist Maria “TooFly” Castillo, who also runs a women’s graffiti collective, beautifully rendered each chapter title. Throughout the book, you’ll find photographs, some previously unpublished, and the work of artists and creators moved to show their love for RBG.

If you want to understand how an underestimated woman changed the world and is still out there doing the work, we got you. If you picked up this book only to learn how to get buff like an octogenarian who can do twenty push-ups, there’s a chapter for you too. We even were lucky enough to wrangle some of the most brilliant legal minds out there to help us annotate key passages from RBG’s legal writing.

RBG has been extraordinary all her life, but she never wanted to be a solo performer. She is committed to bringing up other women and underrepresented people, and to working together with her colleagues even when it seems impossible. We are frankly in awe of what we’ve learned about her, and we’re pretty excited to share it with you.

“I just try to do the good job that I have to the best of my ability, and I really don’t think about whether I’m inspirational. I just do the best I can.”

—RBG, 2015

THIS IS WHAT you should look for on this 90-degree June morning: The broadcast news interns pairing running shoes with their summer business casual, hovering by the Supreme Court’s public information office. They’re waiting to clamber down the marble steps of the court to hand off the opinions to an on-air correspondent. You should count the number of boxes the court officers lay out, because each box holds one or two printed opinions. Big opinions get their own box. This contorted ritual exists because no cameras are allowed inside the court. It jealously guards its traditions and fears grandstanding.

What happens inside the hushed chamber is pure theater. Below the friezes of Moses and Hammurabi, the buzz-cut U.S. marshals scowl the visitors into silence. The justices still have ceramic spittoons at their feet. At 10 A.M. sharp, wait for the buzzer and watch everyone snap to their feet. As a marshal cries “Oyez, oyez, oyez!” watch Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, known around the court as RBG, as she takes her seat at the winged mahogany bench. Look around her neck. When the jabot with scalloped glass beads glitters flat against the top of RBG’s black robe, it’s bad news for liberals. That’s her dissent collar.

On June 25, 2013, RBG’s mirrored dissent collar glinted blue and yellow in reflected light. By then, in her ninth decade of life and her twentieth year on the court, RBG looked fragile and bowed, dwarfed by the black high-backed chair. But people who had counted her out when she had cancer were wrong, both times. People who thought she couldn’t go on after the death of Marty Ginsburg, her husband of fifty-six years, were wrong too. RBG still showed up to do the work of the court without missing a day. She still pulled all-nighters, leaving her clerks voice mails with instructions at two or three in the morning.

The night before had been a long one. From RBG’s perch, third from the right in order of seniority, she sometimes gazed up at the marble columns and wondered to herself if she was really there or if it were all a dream. But that Tuesday morning, her eyes were on her notes. The opinion was long finished, but she had something else to say, and she wanted to get it right. She scribbled intently as Justice Samuel Alito, seated to her left, read two opinions, about land and a bitter custody case involving Indian law. Those were not the cases the cameras were waiting for. It was a two-box day. There was one more left.

Court artist sketch of Shelby County dissent from the bench, June 25, 2013 Art Lien

It was Chief Justice John Roberts’s turn to announce an opinion he had assigned himself. The case was Shelby County v. Holder, a challenge to the constitutionality of a major portion of the Voting Rights Act.

Roberts has an amiable Midwestern affect and a knack for simple but elegant phrases that had served him well when he was a lawyer arguing before the justices. “Any racial discrimination in voting is too much,” Roberts declared that morning. “But our country has changed in the last fifty years.”

One of the most important pieces of civil rights legislation of the twentieth century had been born of violent images: the faces of murdered civil rights activists in Philadelphia, Mississippi; Alabama state troopers shattering the skull of young John Lewis on a bridge in Selma. But for this new challenge to voting rights that came from sixty miles from Selma, Roberts had a more comforting picture to offer the country. High black voter turnout had elected Barack Obama. There were black mayors in Alabama and Mississippi. The protections Congress had reauthorized only a few years earlier were no longer justifiable. Racism was pretty much over now, and everyone could just move on.

RBG waited quietly for her turn. Announcing a majority opinion in the court chamber is custom, but reading aloud in dissent is rare. It’s like pulling the fire alarm, a public shaming of the majority that you want the world to hear. Only twenty-four hours earlier, RBG had sounded the alarm by reading two dissents from the bench, one in an affirmative action case and another for two workplace discrimination cases. As she had condemned “the court’s disregard for the realities of the workplace,” Alito, who had written the majority opinion, had rolled his eyes and shook his head. His behavior was unheard of disrespect at the court.

On the morning of the vot

ing rights case, the woman Alito had replaced, RBG’s close friend Sandra Day O’Connor, sat in the section reserved for VIPs. Roberts said his piece, then added, evenly, “Justice Ginsburg has filed a dissenting opinion.”

RBG’s voice had grown both raspier and fainter, but that morning there was no missing her passion. Alito sat frozen, holding his fist to his cheek. The noble purpose of the Voting Rights Act, RBG said, was to fight voter suppression that lingered, if more subtly. The court’s conservative justices were supposed to care about restraint and defer to Congress, but they had wildly overstepped. “Hubris is a fit word for today’s demolition of the VRA,” RBG had written in her opinion. Killing the Voting Rights Act because it had worked too well, she had added, was like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

At stake, RBG told the courtroom, was “what was once the subject of a dream, the equal citizenship stature of all in our polity, a voice to every voter in our democracy undiluted by race.” It was an obvious reference to Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, but the phrase equal citizenship stature has special meaning to RBG in particular.

Sofia Sanchez and Mauro Mongiello/Trunk Archive

Forty years earlier, RBG had stood before a different set of justices and forced them to see that women were people too in the eyes of the Constitution. That women, along with men, deserved equal citizenship stature, to stand with all the rights and responsibilities that being a citizen meant. As part of a movement inspired by King’s, RBG had gone from having doors slammed in her face to winning five out of six of the women’s rights cases she argued before the Supreme Court. No one—not the firms and judges that had refused to hire a young mother, not the bosses who had forced her out of a job for getting pregnant or paid her less for being a woman—had ever expected her to be sitting up there at the court.

RBG often repeated her mother’s advice that getting angry was a waste of your own time. Even more often, she shared her mother-in-law’s counsel for marriage: that sometimes it helped to be a little deaf. Those words had served her in the bad old days of blatant sexism, through the conservative backlash of the eighties, and on a court of people essentially stuck together for life. But lately, RBG was tired of pretending not to hear. Roberts had arrived with promises of compromise, but a few short years and a handful of 5–4 decisions were swiftly threatening the progress for which she had fought so hard.

That 2012–2013 term, reading dissents from the bench in five cases, RBG broke a half-century-long record among all justices. Her dissent in the voting rights case was the last and the most furious. At nearly 10:30 A.M., RBG quoted Martin Luther King directly: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice,” she said. But then she added her own words: “if there is a steadfast commitment to see the task through to completion.”

Not exactly poetry. But pure RBG. On or off the bench, she has always been steadfast, and when the work is justice, she has every intention to see it to the end. RBG has always been about doing the work.

People wondered where the quiet and seemingly meek RBG had gone, where this firebrand had come from. But the truth is, that woman had always been there.

YOU CAN’T SPELL TRUTH WITHOUT RUTH

* * *

RBG had launched her protest from the bench on the morning of June 25 hoping people outside the court would listen. They did. As it sunk in that the court had, in the words of civil rights hero and Congressman John Lewis, put “a dagger in the heart of the Voting Rights Act,” progressives felt a mix of despair and fury, but also admiration for how RBG had spoken up. “Everyone was angry on the Internet at the same time,” remembers Aminatou Sow. Sow and her friend Frank Chi were both young, D.C. based digital strategists, used to channeling their frustrations into shareable objects. They wanted to do something. Chi spontaneously took a Simmie Knox painting of RBG, with its cool, watchful eyes and taut mouth, and gave it a red background and a crown inspired by the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. Sow gave it words: “Can’t spell truth without Ruth.” They put it on Instagram, then plastered Washington with stickers.

Frank Chi and Aminatou Sow

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, twenty-six-year-old law student Hallie Jay Pope started drawing. Her comic showed RBG patiently explaining to her colleagues what had gone wrong in each case that week. “RBG” finally loses it with “Roberts’s” glib exclamation in Shelby, “LOL racism is fixed!” Pope made an “I Heart RBG” shirt and donated the proceeds to a voting rights organization.

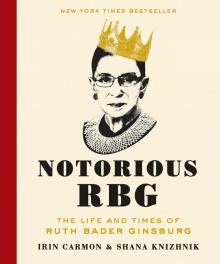

And in New York, twenty-four-year-old NYU law student Shana Knizhnik was aghast at the gutting of voting rights. The only bright spot for her was the unfettered rage of Justice Ginsburg—or, as her classmate Ankur Mandhania jokingly called the justice on Facebook, the Notorious R.B.G. Inspired, Shana took to Tumblr to create a tribute. To her, the reference to the 300-pound deceased rapper Notorious B.I.G. was both tongue-in-cheek and admiring. The humor was in the contrasts—the elite court and the streets, white and black, female and male, octogenarian and died too young. The woman who had never much wanted to make a stir and the man who had left his mark. There were similarities too. Brooklyn. Like the swaggering lyricist, this tiny Jewish grandmother who demanded patience as she spoke could also pack a verbal punch.

Teespring.com

The original Notorious R.B.G. Tumblr postCourtesy of the author

Erie Meyer

These appreciations were just the beginning. RBG, the woman once disdainfully referred to as “schoolmarmish,” the wrong kind of feminist, “a dinosaur,” insufficiently radical, a dull writer, is now a fond hashtag. Her every utterance is clickbait, and according to the headlines, she no longer says anything, but rather “eviscerates.” At least two different Notorious R.B.G. signature cocktails can be drunk in two different cities. Turn on the Cartoon Network and you might glimpse an action figure named Wrath Hover Ginsbot (“appointed for life to kick your butt”). RBG’s face is collaged, painted on fingernails, permanently tattooed on at least three arms, and emblazoned on Valentines and greeting cards with cute puns.

Hundreds of homemade RBG Halloween costumes come in baby and adult forms. By the spring of 2015, RBG was being namechecked anywhere a woman wanted to signal feminist smarts—by comedian Amy Schumer, by Lena Dunham on the show Scandal, and on The Good Wife. Comedian Kate McKinnon made RBG a recurring Saturday Night Live character, who crows each zinger, “Ya just got Gins-burned!” and bumps to a hip-hop beat. “I just want to say that Ruth Bader Ginsburg is one of the most badass women in the world,” Sow announces. “I think people who are no-nonsense people are rewarded greatly by the Internet.”

Nikki Lugo

Ruth “Baby” Ginsburg, also known as Sycamore LivingstonKate Livingston, Sycamore Livingston

RBG greeting cardsAlisa Bobzien

Saturday Night Live’s “Ginsburn”Getty Images/Dana Edelson/NBC

All this is, to use the court’s language, without precedent. No other justice, however scrutinized or respected, has so captured the public’s imagination. The public image of RBG in her over thirty years as a judge was as a restrained moderate. The people closest to RBG find her entrance to the zeitgeist hilarious, if perplexing. “It’s hard for me to think of someone less likely to care about being a cult figure,” says David Schizer, a former RBG clerk and now a friend. “I would not have thought of her as hip,” says her son, James. The adoring portrayal of an older woman like RBG as both fierce and knowing, points out the feminist author Rebecca Traister, is “a crucial expansion of the American imagination with regard to powerful women.” For too long, Traister says, older women have been reduced in our cultural consciousness to “nanas, bubbes” or “ballbusters, nutcrackers, and bitches.” RBG’s old friend Gloria Steinem, who marvels at seeing the justice’s image all over campuses, is happy to see RBG belie Steinem’s own long-standing observation: “Women lose power with age, and men gain it.”

Historically, one way women have l

ost power is by being nudged out the door to make room for someone else. Not long before pop culture discovered RBG, liberal law professors and commentators began telling her the best thing she could do for what she cared about was to quit, so that President Barack Obama could appoint a successor. RBG, ardently devoted to her job, has mostly brushed that dirt off her shoulder. Her refusal to meekly shuffle off the stage has been another public, high-stakes act of defiance.

Seniority determines many of the court’s functions, from the order in which justices speak in meetings to who gets to assign opinions. When Justice John Paul Stevens retired in 2010, RBG became the most senior of the court’s liberals, a leadership role she has embraced. RBG stays because she loves her work, but also, it seems, because she thinks the court is headed in an alarming direction. After years of toil, often in the shadows, she is poised to explain to the country just what is going wrong. “I sense a shift in her willingness to be a public figure,” RBG’s former American Civil Liberties Union colleague Burt Neuborne says. “Perhaps I am a little less tentative than I was when I was a new justice,” RBG told The New Republic in 2014. “But what really changed was the composition of the Court.” It was a polite way of saying the court had lurched to the right.

RBG has never been one to shrink from a challenge. People who think she is hanging on to this world by a thread underestimate her. RBG’s main concession to hitting her late seventies was to give up waterskiing.

Hallie Jay Pope

NOT A BOMB THROWER, BUT A BOMBSHELL ACHIEVER

* * *

Who is Ruth Bader Ginsburg? She takes her time, but nothing is lost on her. “She’s not just deliberative as a matter of principle but as a matter of temperament,” her friend the critic Leon Wieseltier has said. “A conversation with her is a special pleasure because there are no words that are not preceded by thoughts.” She is wholly committed, above all, to the work of the court. Kathleen Peratis, who succeeded RBG as director of the Women’s Rights Project at the ACLU, said years ago, “Ruth is almost pure work. The anecdote that describes her best is that there are no anecdotes.” (The second part is not strictly true.) She has survived tragedies and calamities. People have found her somber, but it is sometimes because her humor is so deadpan dry that it escapes many. She can be exacting, but rewards with loyalty and generosity. She had a passionate love affair with her husband that lasted almost sixty years.

Notorious RBG

Notorious RBG